By Raquel Gilliland and Breilly Roy, Sea of Change Foundation interns

Welcome to our new series “Creature Features” where we’ll briefly introduce you to some fascinating facts about a sea creature, why it is special and unique, and its conservation status.

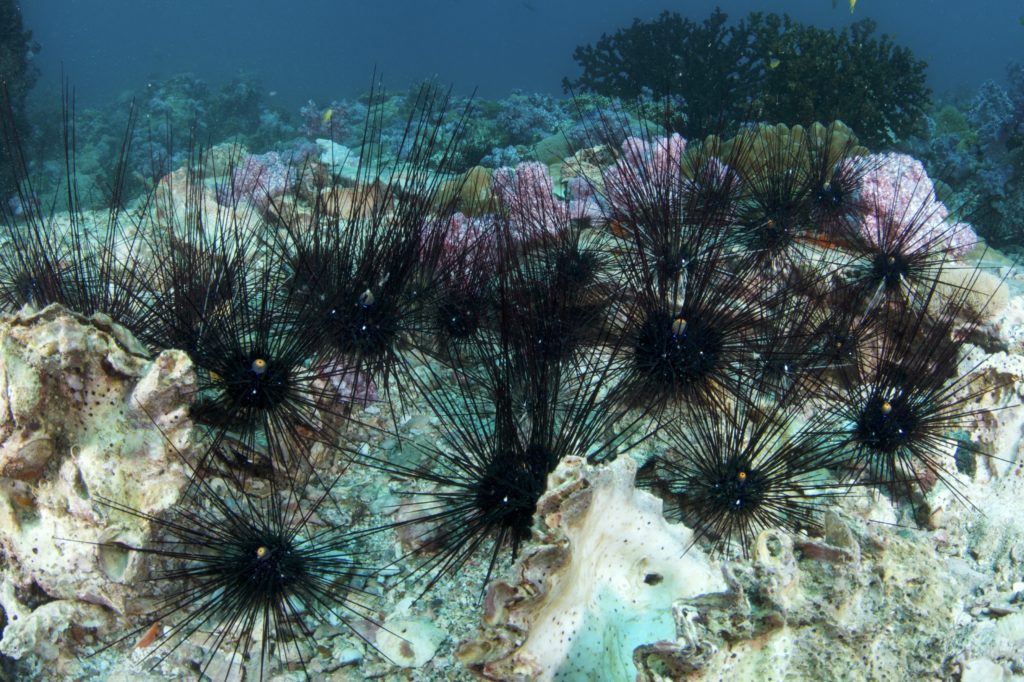

This week’s creature is the long-spined or black sea urchin (Diadema antillarum), a sharp specimen that hides in small crevices along the reef. They belong to the phylum Echinodermata – exclusively marine invertebrates that are characterized by a hard, spiny covering or skin, and that also includes other familiar reef residents such as sea stars, sand dollars and feather stars. They have a test or “shell” with venomous spines that grow as long as 10-12cm. Their ventral (underneath their bodies) scraping mouths were originally described by Aristotle as being lantern-shaped and scientists today still refer to them as “Aristotle’s lantern”.

Their habitats are crevices in coral reefs at depths of 1-10 meters deep. These creatures are nocturnal and feed mainly on algae; and they, in turn, are a favorite food of queen triggerfish (Balistes vetula) that use their powerful jaws to pull out the spines and break the test. The urchins’ role in a healthy reef ecosystem is to graze on algae that otherwise can outcompete corals for limited space to settle and grow. Unfortunately, in the early 1980’s there was a significant die off of long-spined urchins due to disease with 90% of the species being wipe out throughout Florida, the Caribbean and Bermuda from which many reefs in the region are still recovering.

Given that Diadema produce many eggs, their slow recovery from the disease outbreak almost 30 years ago has long puzzled scientists. Recently, researchers from Scripps Institution of Oceanography found that when staghorn coral (Acropora cervicorni) – a threatened species on the U.S. Endangered Species List – populations increase, Diadema populations decrease. They theorized that the reason for this could be the aggressive and territorial behavior of the threespot damselfish (Stegastes planifrons) that competes with Diadema for algae grazing patches on the reef. “These damselfish pick up urchins and move them off the coral with their mouths,” said Cramer, a postdoctoral scholar at Scripps and lead author of the study. “Damselfish populations appear to have grown recently as their predators have been overfished, which is one plausible explanation as to why long-spined urchin populations have failed to recover.”

Currently, the global conservation status of these urchins has not been evaluated by the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) Red List, they have no special status under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, and under CITES (the Convention in International Trade in Endangered Species) they are also not protected from collection nor international trade.

Given their vital role in coral reef recovery and resilience, we hope to see populations of important reef grazerscome back in full force. You can learn more about how the Sea of Change Foundation has helped support research to reintroduce long-spine sea urchins to the reefs of the Bahamas, here; Reversing the Decline of Bahamian Coral Reefs – Herbivory Study, 2018.

Please consider supporting the Sea of Change Foundation as we work to create positive change for the oceans we all love to dive and explore. DONATE HERE. Thank you.